Dominic Johnson, from the Queen Mary University of London, is interested in work around touch and one-to-one performances. In 2012 he interviewed Adrian Howells, a well-known one-to-one performer. Unfortunately, Adrian Howells died before the publication of his interview*.

In another tone, my classmate and I were asked to answer some of the questions of the interview, as artists (or artists-to-be).

The interview

- Speaking as an artist and also as an audience member, what do you think makes an effective performance? What do you look in performance?

Both as an artist and as an audience member, I am looking for images. Images can be optical, visual or audiovisual, when considering the colors, the lights, the costumes, the music – with all the factors that will make the performance a spectacle. Spectacle can be different from a simple view of something and certainly it can be different for different point of views. For me a spectacle is always unexpected, it is unique and it always attracts attention or interest. It is images that are, also, transformed easily to experiences, such as memories, messages within the performance and feelings. An effective performance for me is something I will remember. And definitely something that I will want to remember.

- Have you yourself been concerned that the departures you have undertaken somehow make the work unreadable or unrecognizable as aesthetic projects?

My background is focused on dance, theatre and music (piano and voice). I feel that all these contribute to an understandable performance. Even if I separate them, I always try to find this element that is going to make the performance readable. At least one element, for the audience to have something to take back home. If I know I can achieve that, I won’t be concerned.

During my MA Choreography semesters I got challenged with choreographical methods I considered unreadable for the audience, such as improvisation-based choreography and performance art. I was always thinking that “the audience will not like it, because they won’t understand it”. One thing I learnt is that the audience doesn’t know what they like, they rarely know what they understand, but they do know that they are there, in the theatre, waiting to watch something that will change their lives and make them think and feel closer to the dancers.

- Can you tell me about how you develop and refine the aesthetic aspects of your work?

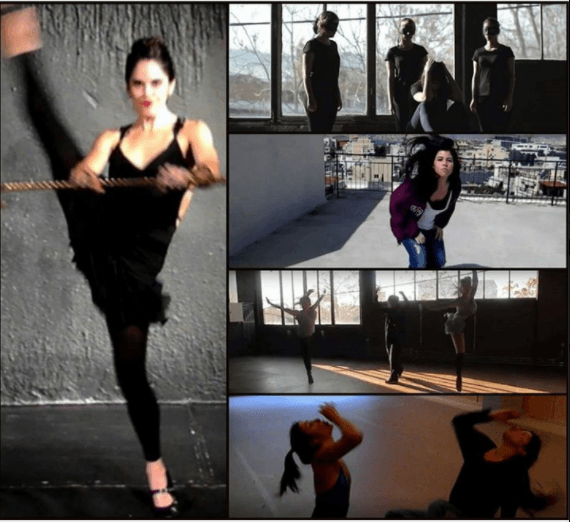

First of all, I am inspired by things I want to say. For example, my audition videos were dance-related autobiographical stories. Maybe the music will help me in that. Or maybe I will have some criteria, as to re-stage/re-choreograph one of the Seven Easy Pieces of Marina Abramovic. Moreover, I always want my dancers to be good actors. I prefer them not doing a triple pirouette, if they can work with their face and body expression. I always want them to have stamina and never look exhausted. I dedicate a good amount of rehearsals to help them improve their stamina and acting-training. Then, it is also my touch, what I always want to see in a choreography: a story. Maybe a humorous one or a powerful one. And if I see that, I can then create a spectacle, with lights, costumes and beautiful dancers/ story-tellers.

The piece I am currently working on, “Re:patterning” , can be considered unreadable, as we said before. The dancers have understood that the stamina is very important in this piece. They have given their own meaning to their lines and their movement. They have even given different meanings to the different tasks. I don’t consider the work as “dance choreography”, though the dancers are engaged with some. It can be even criticised as simple and “just fine”, but there is something behind it. There is a message I want the audience to grasp. There are characters that I want the audience to find similar to themselves. And I want them to discover that there are some rituals and endurance practices that they, too, go through simply every day.

- What is the place of the contract – social or unwritten- in your performance? How do you deal with unwritten agreements or limitations, which all performances potentially entertain?

To be honest, I would never create an environment where the audience would feel uncomfortable. But this is something I cannot always control. I encourage the dancers to feel uncomfortable sometimes, only in the way that they could achieve something for themselves, like climbing on an unstable door (with all the necessary precautions of course), or try some out-of-comfort-zone sensual moves. However, I always respect their limits and always come up with other moves that they will be proudly executing.

As for the audience, I believe in the distance and the comfort. We live in a society where we have to be touched to be liked. I find this important, because, in order to achieve, we have to show our flesh and even remove our boundaries and become something we are not. Do we want to get promoted or famous or land a job? Most of the times, we are to be touched. But, what if we don’t like to be touched? Physically or in social media or by friends or by strangers? Only in distance you can make the decision “do I want to approach or not?”. Approach physically or emotionally or mentally or psychologically. There are performances that on purpose want to test these limits; where people go willingly to pass that test. I want the audience to approach the work in their own way. And it will be a willing decision, I assure you.

*Johnson, D. (2012) The Kindness of Strangers: An Interview with Adrian Howells. Performing Ethos, 3(2) 173-190