One-to-one performances can be difficult. They are rather difficult to set, too. There are the ethical implications and then there are all these elements that have to be connected or else something is missing and the engagement will be lost.

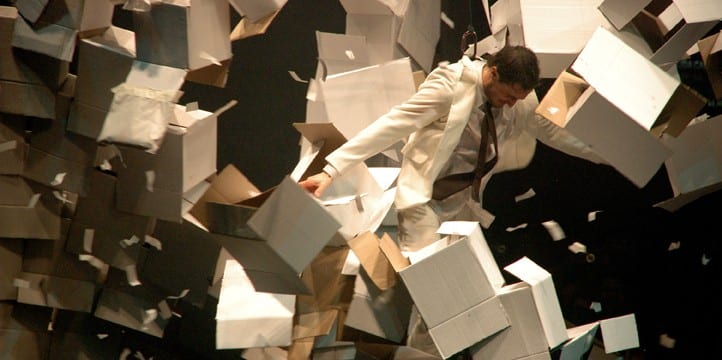

I tried to create a connecting, interactive dance environment for a term A module and it slightly backfired. I just was not ready yet to construct an environment and a choreography that would be engaging, intimate and maybe touching.

After all the readings, there is a word worth keeping in mind while creating a choreography or a performance: connection. Connection makes the work.[1]

But then, there are some other words that appear in the readings’ vocabulary:

- COERCION

- INTROJECTION: the unconscious adoption of another’s thoughts and ideas

- HUMANITY

- INTIMACY

All work their way more or less to the connection, the collaboration between the performer and the participant.

And this is something that happens only in a one-to-one performance, as Adrian Howells says[2] , while he completely disagrees with the theatrical performances of 700 people watching him and connecting with him

Well, I disagree with him.

“Personal insecurities and digressions have the potential to produce

more intimate connections to the “integrity experience”,

through “immediacy”, “relationship”, “awareness” and “attention”1”.

A crowded theatrical or dance performance can create intimate connections because of the integrity experience, through the immediacy, the relationship, the awareness and the attention, and mainly because of the personal insecurities that the audience carries while sitting in front of the stage.

Undoubtedly, crowded performances differ from one-to-one performances in the aspect of the safety and trust among the audience members (higher in crowded performances, when they enjoy a show with friends and relatives) and the self-consciousness of the participants (higher in a one-to-one performance, where they desire to “give a good audience”1).

There is a connection made during a live performance. How intimate it is, is negotiable. However, it would seem inappropriate to flatten so many performers’, dancers’, actors’ work and effort to create emotion, to transmit a message to or to inspire their audience.

Following that, Marina Abramovic appeared to disagree with me by saying: “Theatre is fake (…). The knife is not real, the blood is not real and the emotions are not real. Performance is just the opposite: the knife is real, the blood is real and the emotions are real” (O’Hagan 2010:32)2.

Answering that, Simon Murray and John Keefe in their book “Physical Theatres: critical introduction” (2007) write that “the real never went away and never goes away. Such debates can become facile in their danger of removing the real from discourse, experience from rhetoric; making the lived experience of the body a mere plaything for theoreticians’ ping-pong”.[3]

After that, I’m thinking about the poor Stanislavski and all his theory on “becoming” the character, the training exercises, the methodology and the pain actors have endured when finally reaching the stage of “becoming the character”. I’m thinking about them performing – actually performing– with tears and sweat and blood. How fake and artificial can this be?

I’m wondering, is it because they don’t use the knife for real? Is it because they don’t cut themselves for real? And I’m wondering more, should actors harm themselves every time they go on stage so that the audience see something real? What if their characters get killed? What if their characters lose their virginity or get raped? What if they have to be hung? What if the director is artistically mental and wants to see blood everywhere and the actors suffer from HIV and it is harmful for their personal lives? Then what?

And this leads my thoughts to ancient Greek tragedies where death or blood battles or anything harmful was just narrated and never performed on stage because of the ethics and the ennoblement of the writers’ work.

It is a peculiar era we are living nowadays. An era where nudity, sex and massacres are okay to be watched on TV and cinema and then transferred on stage and books and then becoming a reality, which we have to accept if we want to be part of this society, if we want to be “liked” and accepted (or better approved?) .

So, then, what is real and what is fake? What is truly intimate without being coerced?

Let’s create some more definitions and we can talk about it in a few years.

– – – – – –

[1] Heddon, D., Iball, H. and Zeriham, R. (2012) Come Closer: Confessions of Intimate Spectators in One to One Performance. Contemporary Theatre Review, 22(1) 120 – 133. [2] Johnson, D. (2012) The Kindness of Strangers: An Interview with Adrian Howells. Performing Ethos, 3(2) 173-190. [3] Murray, S. & Keefe, J. (2007). Physical Theatres: A critical introduction. Routledge: London & New York. p.60