6.1 Boalian perspectives on interactivity in theatre

By John Somers (pp. 148-156)

- “(…) Fiction is vitally important – indeed we may live more by fiction than by fact. It is living by fiction which makes the higher organisms special” (Gregory, in Roses 1985:16)

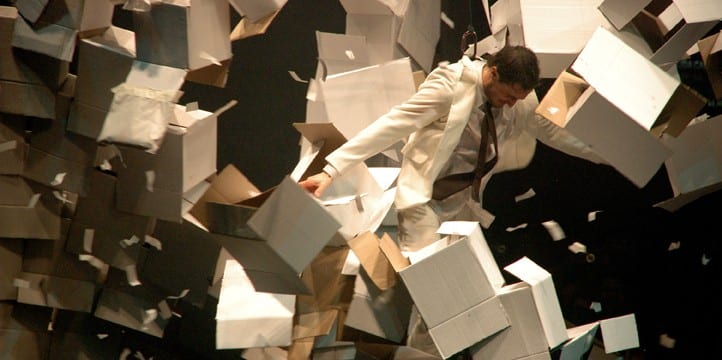

- Boal’s principal contribution [to interactive theatre] was to remove the “fourth wall”, which in most theatre forms through time had clearly separated audience and actor spaces.

- The artist may make forays into the auditorium or invite audience members into their space. Typically, this happens when magicians or stand-up comedians perform. They can see and talk directly to the audience.

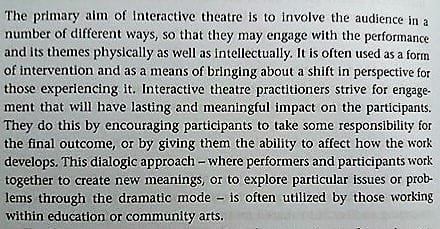

- Key areas of concern:

- Sincerity: where an audience is invited to become involved in the affairs of performed characters, they need to feel that they will not be taken advantage of

- Targeting: interactive theatre is often targeted at specific, generally homogenous groups

- Authenticity: the programme developers have to conduct rigorous research on the topic they wish to deal with

- Relevance: the research should also reveal what the target group will find relevant to their personal or professional lives.

- Validation: audience members are more likely to become engaged with the story if it validates their experience

- Audience size: the audience numbers are restricted; it is more difficult to engage the moral concern of very large groups

- The style of acting used in interactive theatre may be highly naturalistic. Actors must remain alert and respond in role to audience demands and suggestions.

6.2 Interactivity at the work of Blast Theory

Matt Adams in conversation with Alice O’Grady (pp.156-165)

“Interactive work has to be unfinished”

-Brian Eno

Pitches, J., and Popat, S. (ed.) (2011) Performance Perspectives: A Critical Introduction. New York: Palgrave Macmillan